Pixar and the Pope: Pope Francis’ Laudato Si’ and Pixar’s Wall-E

The pope’s new eco-encyclical and the classic Pixar film share a number of environmental, economic and spiritual themes.

Reading Pope Francis’ new encyclical Laudato Si’ “on care for our common home,” I find myself wanting to sit down and revisit one of my favorite animated films: Pixar’s Wall-E (2008), directed by Andrew Stanton. (It doesn’t hurt that this weekend’s theatrical release of Inside Out, Pixar’s most visually stunning film since Wall-E, already has me in a Pixary mood.)

“The earth, our home, is beginning to look more and more like an immense pile of filth,” Pope Francis writes. “In many parts of the planet, the elderly lament that once beautiful landscapes are now covered with rubbish” (LS 21).

From the outset Wall-E looks as if it had been created with these words in mind, projecting them into a dystopian future in which rubbish has expanded to cover the entire planet, even surrounding the Earth in a halo of space debris. Towering heaps of compressed trash dominate the film’s landscapes, collected and stacked into skyscraper-like structures by armies of trash-compacting robots, of which only a single unit remains functional: our Wall-E (“Waste Allocation Load Lifter Earth-class”).

In this world there are no elderly to lament the landscape, for the human race has abandoned the Earth and now inhabits an immense, cruise ship–like spaceship called the Axiom. It is supposed that mankind will return to Earth once it has become habitable again, though in reality powerful elites — specifically, the leadership of the mega-corporation Buy n Large (BnL), which is responsible for Earth’s ravaged condition, the Wall-E units and the Axiom — have secretly concluded that the Earth has become too toxic to ever be habitable again. They’re wrong, but the Earth’s sad condition nevertheless reflects Pope Francis’ diagnosis regarding “symptoms of sickness evident in the soil, in the water, in the air and in all forms of life” (LS 2).

Looking more closely, a poisoned environment and landscapes covered with rubbish are far from the only points of contact between Wall-E and Laudato Si’. Among other common themes are the following.

Consumerism

Wall-E is largely a social satire of overconsumption and corporate greed run amok. Seven centuries after mankind has abandoned the Earth, automated holographic billboards advertising BnL products still bear witness to the economic forces that destroyed the Earth.

On board the Axiom, mankind has regressed to a state of infant-like passivity, never rising from mobile hoverchairs, never looking up from their holo-screens. Every other value has been sacrificed for convenience (“Lunch…in a cup!”). With Pavlovian responsiveness, the population follow every marketing trend that comes along (“Try blue — it’s the new red!”).

This picture resonates with the roots of environmental threats described by Pope Francis in Laudato Si’:

Since the market tends to promote extreme consumerism in an effort to sell its products, people can easily get caught up in a whirlwind of needless buying and spending. Compulsive consumerism is one example of how the techno-economic paradigm affects individuals. Romano Guardini had already foreseen this: “The gadgets and technics forced upon him by the patterns of machine production and of abstract planning mass man accepts quite simply; they are the forms of life itself. To either a greater or lesser degree mass man is convinced that his conformity is both reasonable and just”. This paradigm leads people to believe that they are free as long as they have the supposed freedom to consume. But those really free are the minority who wield economic and financial power. Amid this confusion, postmodern humanity has not yet achieved a new self-awareness capable of offering guidance and direction, and this lack of identity is a source of anxiety. We have too many means and only a few insubstantial ends. (LS 203)

Quality of human life and social breakdown

The satiric picture of the Axiom residents with their eyes glued to their holo-screens — so isolated from others all around them that it comes as a shock when (through Wall-E’s destabilizing influence) a man and a woman named John and Mary actually start to look around and encounter one another — finds a parallel in the pope’s words:

Real relationships with others, with all the challenges they entail, now tend to be replaced by a type of internet communication which enables us to choose or eliminate relationships at whim, thus giving rise to a new type of contrived emotion which has more to do with devices and displays than with other people and with nature. Today’s media do enable us to communicate and to share our knowledge and affections. Yet at times they also shield us from direct contact with the pain, the fears and the joys of others and the complexity of their personal experiences. For this reason, we should be concerned that, alongside the exciting possibilities offered by these media, a deep and melancholic dissatisfaction with interpersonal relations, or a harmful sense of isolation, can also arise. (LS 47)

It isn’t only each other that the Axiom residents are isolated from. In their luxury starliner, cruising through cavernous spaces enclosed in steel and glass and other artificial materials, mankind has no connection to the natural world: grass, trees, plants, animals, even dirt. It is an utterly sterile environment; any sign of a “foreign contaminant” is obliterated by a vigilant bot named Mo. There is a swimming pool, but residents have long since forgotten about its existence.

While the urban environments Pope Francis describes are much less pleasant and hygienic than the Axiom, his conclusion applies equally to both:

Many cities are huge, inefficient structures, excessively wasteful of energy and water. Neighbourhoods, even those recently built, are congested, chaotic and lacking in sufficient green space. We were not meant to be inundated by cement, asphalt, glass and metal, and deprived of physical contact with nature. (LS 44)

Work, technology and human dignity

Part of the dystopian crisis on the Axiom is that man as consumer has entirely replaced man as laborer and producer. BnL robots do all the work of providing for mankind; human beings do nothing for themselves. After centuries of passivity — combined with the deleterious effects of microgravity on bone density — human beings have become blob-like functional babies, nearly unable to stand or think for themselves.

For Pope Francis, “an integral ecology” is inseparable from concerns about human well-being generally, including concern about labor: “Any approach to an integral ecology, which by definition does not exclude human beings, needs to take account of the value of labour” (LS 124). Threats to labor from technology are a significant concern for the pope:

We were created with a vocation to work. The goal should not be that technological progress increasingly replace human work, for this would be detrimental to humanity. Work is a necessity, part of the meaning of life on this earth, a path to growth, human development and personal fulfilment …Yet the orientation of the economy has favoured a kind of technological progress in which the costs of production are reduced by laying off workers and replacing them with machines. This is yet another way in which we can end up working against ourselves. The loss of jobs also has a negative impact on the economy “through the progressive erosion of social capital: the network of relationships of trust, dependability, and respect for rules, all of which are indispensable for any form of civil coexistence”. In other words, “human costs always include economic costs, and economic dysfunctions always involve human costs”. To stop investing in people, in order to gain greater short-term financial gain, is bad business for society. (LS 128)

Although Wall-E doesn’t explore the “bad business” implications, its illusory consumerist paradise would surely be ultimately unsustainable. A society bereft of human creativity and energy is doomed.

Not surprisingly, Laudato Si’ expresses special concern for the poor and disenfranchised, noting that it is the wealthy who disproportionately consume the Earth’s resources, and the poor who disproportionately suffer from harm to the environment (LS 25, 51). Environmental initiatives must not be pursued in a way that crushes the development of poorer nations, the pope argues (LS 52, 175).

Although there is no indication of human poverty or privation in the Axiom’s utopian dystopia, the general theme of disenfranchisement finds metaphorical expression in the “reject bots” — misfit robots from mankind’s mechanical servant class who, at Wall-E’s not entirely intentional instigation, rise up against the oppressive system that has enslaved them.

It is significant that Laudato Si’ rejects a Malthusian approach to environmentalism that regards population growth as a threat to be controlled. From the outset the pope declares, “Human beings too are creatures of this world, enjoying a right to life and happiness, and endowed with unique dignity” (LS 43). Abortion in particular Pope Francis sees a symptom of consumerist “throw-away” culture (LS 120–123). He also states:

Instead of resolving the problems of the poor and thinking of how the world can be different, some can only propose a reduction in the birth rate … To blame population growth instead of extreme and selective consumerism on the part of some, is one way of refusing to face the issues. It is an attempt to legitimize the present model of distribution, where a minority believes that it has the right to consume in a way which can never be universalized, since the planet could not even contain the waste products of such consumption. (LS 50)

This pro-humanistic perspective is reflected in Wall-E’s final act, not only in mankind’s hopeful return to Earth, but in an adorable moment that suggests that — after generations of children apparently being raised by BnL, presumably involving some form of artificial reproduction — mankind is ready to return to family life: At a moment of high crisis, John and Mary throw their arms protectively around a gaggle of imperiled babies. “John,” Mary cries moments earlier, “get ready to have some kids!”

Wonder, spirituality, love and faith

Although little Wall-E was created for the sole purpose of dealing with the consequences of mankind’s environmental irresponsibility, he is not defined by this task. On the contrary, Wall-E is essentially a love story.

Reflecting the image of his creator, man, Wall-E’s work among the detritus of human culture has awakened in him curiosity, wonder and longing. Studying artifacts from Rubik’s Cubes to ring boxes, Wall-E implicitly seeks understanding of his makers, just as men seek understanding of God by studying creation. Above all, the robot’s fascination an old VHS copy of the Gene Kelly musical “Hello, Dolly!” (1969) has instilled him with aesthetic sensibilities and incipient romantic yearning.

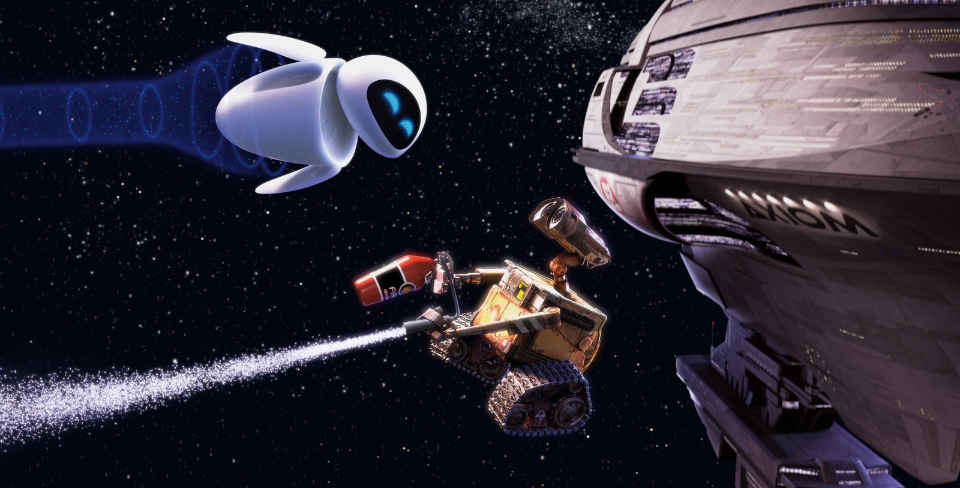

One day, without warning, Wall-E’s existence is changed forever when he is visited by incomprehensible power and glory from the unguessed heavens, which he has difficulty seeing due to the debris cloud surrounding the Earth. Not many Hollywood cartoons traffic in themes of awe, mystery and existential terror, but for Wall-E the thunderous arrival of an immense spaceship, followed by the stunning appearance of a vision of grace, elegance and dread in the form of the robot EVE (Extraterrestrial Vegetation Evaluator), is as transformative an experience as the hominid tribe’s first encounter with the primordial monolith in “2001: A Space Odyssey” (1968).

Wall-E is in love — and love lifts him up, to his terror and wonder, into the heavens as he rides EVE’s rocket ship into space, where he beholds stars clearly for the first time. In time, not only does Wall-E’s devotion to EVE eventually elicit similar feelings in her, he winds up playing a key role in the fulfillment of her mission regarding the Earth’s fertility. EVE has been tasked with identifying and verifying any sign that the Earth is able to support life again, and a small seedling, first found by Wall-E and later repeatedly saved by him, ultimately leads to mankind’s return to its native home.

Citing the example of Saint Francis of Assisi, Laudato Si’ likewise connects “an integral ecology” to openness to wonder, awe, mystery, love, spiritual openness and even song:

Francis [of Assisi] helps us to see that an integral ecology calls for openness to categories which transcend the language of mathematics and biology, and take us to the heart of what it is to be human. Just as happens when we fall in love with someone, whenever he would gaze at the sun, the moon or the smallest of animals, he burst into song, drawing all other creatures into his praise. He communed with all creation, even preaching to the flowers, inviting them “to praise the Lord, just as if they were endowed with reason” … If we approach nature and the environment without this openness to awe and wonder, if we no longer speak the language of fraternity and beauty in our relationship with the world, our attitude will be that of masters, consumers, ruthless exploiters, unable to set limits on their immediate needs…

What is more, Saint Francis, faithful to Scripture, invites us to see nature as a magnificent book in which God speaks to us and grants us a glimpse of his infinite beauty and goodness. “Through the greatness and the beauty of creatures one comes to know by analogy their maker” (Wis 13:5); indeed, “his eternal power and divinity have been made known through his works since the creation of the world” (Rom 1:20). For this reason, Francis asked that part of the friary garden always be left untouched, so that wild flowers and herbs could grow there, and those who saw them could raise their minds to God, the Creator of such beauty. Rather than a problem to be solved, the world is a joyful mystery to be contemplated with gladness and praise. (LS 11–12)

Humanity and hope

Grim as the human condition aboard the Axiom is, mankind bounces back at the end with surprising resilience, returning to Earth and attempting with gusto to embrace a simpler, more agrarian lifestyle less dominated by consumption.

This hopeful picture resonates with Pope Francis’ words of hope in latter passages of Laudato Si’:

Yet all is not lost. Human beings, while capable of the worst, are also capable of rising above themselves, choosing again what is good, and making a new start, despite their mental and social conditioning. We are able to take an honest look at ourselves, to acknowledge our deep dissatisfaction, and to embark on new paths to authentic freedom. No system can completely suppress our openness to what is good, true and beautiful, or our God-given ability to respond to his grace at work deep in our hearts. I appeal to everyone throughout the world not to forget this dignity which is ours. No one has the right to take it from us. (LS 205)

Christian spirituality proposes an alternative understanding of the quality of life, and encourages a prophetic and contemplative lifestyle, one capable of deep enjoyment free of the obsession with consumption. We need to take up an ancient lesson, found in different religious traditions and also in the Bible. It is the conviction that “less is more”. A constant flood of new consumer goods can baffle the heart and prevent us from cherishing each thing and each moment. To be serenely present to each reality, however small it may be, opens us to much greater horizons of understanding and personal fulfilment. Christian spirituality proposes a growth marked by moderation and the capacity to be happy with little. It is a return to that simplicity which allows us to stop and appreciate the small things, to be grateful for the opportunities which life affords us, to be spiritually detached from what we possess, and not to succumb to sadness for what we lack. (LS 222)

Our common home

From infancy, residents of the Axiom are taught that the ship is their “home sweet home.” They have practically forgotten that their true home — our common home, as Pope Francis reminds us over and over in Laudato Si’ — is the Earth.

At last, through the help of Wall-E and EVE, the ship’s captain slowly opens his eyes to the situation and reacquaints himself with all that the human race has left behind, from dancing and farming to pizza and oceans.

In the end the captain realizes that action is necessary, that mankind can no longer continue on auto-pilot — literally so, for the Axiom is piloted by a system named Auto that, on orders from BnL, refuses to return to Earth.

“Out there is our home!” the captain declares firmly. “Home, Auto! And it’s in trouble! I can’t just sit here and…and…do nothing!”

This, of course, is very much what Pope Francis is telling us: The Earth, our common home, is in trouble. We can’t just do nothing.

Related

WALL•E (2008)

Even Pixar has never attempted anything on a canvas of this scale. From Monsters, Inc.’s corporate culture to Finding Nemo’s submarine suburbia, previous Pixar films have never strayed too far from the rhythms of real life. … WALL‑E creates a world that, despite clear connections to contemporary culture, looks and feels nothing like life as we know it, with unprecedented dramatic and philosophical scope.

Recent

- Benoit Blanc goes to church: Mysteries and faith in Wake Up Dead Man

- Are there too many Jesus movies?

- Antidote to the digital revolution: Carlo Acutis: Roadmap to Reality

- “Not I, But God”: Interview with Carlo Acutis: Roadmap to Reality director Tim Moriarty

- Gunn’s Superman is silly and sincere, and that’s good. It could be smarter.

Home Video

Copyright © 2000– Steven D. Greydanus. All rights reserved.