Three Phases of Pixar History

Peter Chattaway has just posted some thoughts he’s previously shared elsewhere regarding the shape of Pixar’s body of work to date, and I’ve long thought it’s a brilliant theory. In essence, he proposes three phases of Pixar history, which might be labeled thus:

- the “Disney distribution” phase, consisting of the first seven films up to Cars, which were all made under contract for distribution by Disney;

- a transitional “looking beyond Disney” phase, consisting of the next three films — Ratatouille, WALL-E and Up — which may well have gone into development at a point when Pixar believed they were likely to part ways with Disney; and

- the “Disney purchase” phase, consisting of Pixar’s roster of coming films — Toy Story 3, Cars 2, Monsters Inc. 2 and The Bear and the Bow (or Brave?) — all of which began life very much under the Disney umbrella, either by Disney itself or by Pixar after it was purchased by Disney.

What makes this theory so interesting is the way it illuminates the differences between the films belonging to each of the three phases. I’m not sure it’s entirely persuasive to say, as Peter does, that the three phase 2 films, initiated when Pixar was likely thinking outside the Disney box, necessarily “aim higher” than the seven films of phase 1. In particular, I think The Incredibles aims as high as any film in Pixar’s oeuvre.

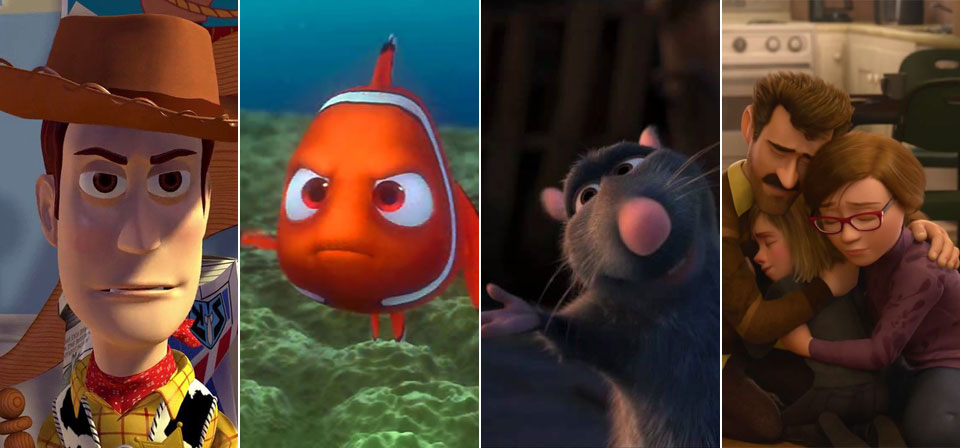

I would put it this way: The basic premise of each of Pixar’s first seven films fits comfortably within mainstream expectations for Hollywood animated family films. Anthropomorphic toys, bugs or cars; friendly monsters saddled with a human child; a father-and-son fish story; even a family of incognito super heroes — these are all concepts that could easily be pitched to Disney execs without making anyone blink or sweat. Pixar might take these concepts in brilliant directions, but there’s nothing about the basic concept of any of these films that especially pushes the envelope of family entertainment.

With the next three films, on the other hand, there is something audacious and outside-the-box about the premise itself, in terms of family-film expectations. A talky picture about a French rat who wants to be a chef? A substantially dialogue-free slapstick adventure about a lone robot in a post-apocalyptic world of trash? An elderly widower absconding with his house via balloon to South America? None of these hits you over the head as a ready-made idea for an animated family film. There is something counter-intuitive about each of them. Here is where Pixar pushes the envelope, not just in terms of how to make a animated family film, but even what it is possible for an animated Hollywood family film to be.

Now, though, we’re entering the Pixar purchase phase. Many Pixar fans were reassured when Disney’s acquisition of Pixar put John Lasseter in charge of Disney animation, suggesting that far from Disney cramping Pixar’s style, Pixar might bring its creative magic to Disney. (And in fact, as Peter points out, Disney’s Bolt does play as “Pixar lite,” though the subsequent The Princess and the Frog is pure Disney, competent but not elevated.) This seemed further confirmed when Lasseter announced he was pulling the plug on Disney’s development work on Toy Story 3 (which Disney, holding sequel rights, had been planning to do themselves if Pixar walked).

But then Lasseter reversed himself on Toy Story 3 — and then followed up with two more sequels to phase 1 Pixar projects — followed by an original film that’s been pitched as “Pixar’s first fairy tale.” In other words, Pixar’s roster of coming films are all well within the “Disney box.” They may turn out to be excellent films and worthy successors to their predecessors, but there’s nothing envelope-pushing about any of them.

I don’t necessarily mind Pixar going back to its roots in this way, although I’m not sure we needed three sequels in a row (or that we needed a sequel to Cars at all). Advance buzz on Toy Story 3 is at least encouraging (see Peter’s post for more), and I wouldn’t be surprised if Monsters Inc. 2 were more or less as good as its predecessor — or if Cars 2 were better.

But I’d hate to see the genre-bending audacity of those three phase 2 pictures disappear. It was those three films that established Pixar as more than the 800-pound gorilla of Hollywood family entertainment. WALL-E and Up, especially, challenged family audiences to go way beyond their homogenized comfort zone, to deal with themes, styles and rhythms that no one else in Hollywood would even think of offering them. For that, I love these films unreservedly, regardless what critical objections anyone might want to make to either film. I hope Pixar comes back to this too, by which I mean I hope that they make movies as unlike WALL-E and Up as WALL-E and Up are unlike everything else in Pixar’s oeuvre. (I am not jonesing WALL-E 2 or Up 2.)

Meanwhile, if Pixar must make sequels to their first seven films, why is no one talking about the one Pixar film that most cries out for a sequel? I mean, of course, The Incredibles. I understand that Brad Bird is a busy guy, but what’s he doing after 1906? Please tell me someone in Emeryville is asking this question.

P.S. And now Peter has posted a response to this post with some interesting thoughts about Pixar and the Beatles, The Princess and the Frog and John Lasseter — and Brad Bird and an Incredibles sequel. Suffice to say, 1906 can’t come soon enough!

Link: All Pixar reviews

Related

Three ages of Pixar

For 15 astonishing years, from 1995 to 2009, Pixar created a body of work — 10 films — so revolutionary and beyond mainstream Hollywood animation that it’s hard to quantify … In recent years, alas, Pixar has stumbled more often than not.

What’s so special about Pixar’s flawed protagonists and their moral journeys

Only Pixar regularly impresses on viewers that just because you’re the hero of your story doesn’t mean you’re right about everything: that you may make serious mistakes, there may be consequences, and you must take responsibility.

In Praise of Pixar Short Films

One of the more striking marks of Pixar’s innovative stature and impact on the world of Hollywood animation has been their pioneering revival of the long-neglected animated short film prior to the feature (at least prior to animated features) as an industry staple.

Recent

- Benoit Blanc goes to church: Mysteries and faith in Wake Up Dead Man

- Are there too many Jesus movies?

- Antidote to the digital revolution: Carlo Acutis: Roadmap to Reality

- “Not I, But God”: Interview with Carlo Acutis: Roadmap to Reality director Tim Moriarty

- Gunn’s Superman is silly and sincere, and that’s good. It could be smarter.

Home Video

Copyright © 2000– Steven D. Greydanus. All rights reserved.