Reviews

Angels & Demons (2009)

Once you’ve established that your story is set in a world in which Jesus Christ is explicitly not God, and the Catholic religion is a known fraud perpetuated by murder and cover-ups, it sort of sucks the wind out of whatever story it was you were going to tell us next. Langdon could be ironing his chinos and helping little old ladies across the street, and it would still be set in that world, and those of us who care about such things will find it hard to bracket that and just go along with the thrill machine.

Star Trek (2009)

And so, for the first time in forever, we have Star Trek really and truly boldly going where we haven’t been before — taking Kirk, Spock, Bones, Uhura, Scotty, Sulu and Checkov on a brand-new adventure for the very first time. Before you know it, you’re getting to know old friends in an entirely new light. It’s like what Alan Moore said about Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns: “Everything is exactly the same, except for the fact that it’s all completely different.”

X-Men Origins: Wolverine (2009)

If you’re a fan of the material, you’ll want to see it. There are some decent action scenes, and an inevitable, tragic climax. There are also things that make no sense. It’s not bad, really. What it’s most conspicuously lacking is any sense of surprise, of revelation, of creative boldness.

Battle for Terra (2009)

Watching Battle for Terra, the latest computer-animated offering presented in 3D, is little like stepping into a breathtaking cathedral in a strange city and finding a church play going on in the middle of it. The drama may be competently done, but it’s the least interesting thing in the room. You keep looking past the action, stealing glances to one side or the other, absorbed in the splendor of the setting. Earnest as the players are, the moralizing story draws you in only fitfully, and most of the time you’d rather steal away and just wander aimlessly from one corner to another, taking it all in.

The Soloist (2009)

The Soloist is a story about a relationship across a socioeconomic chasm. Steve Lopez (Robert Downey Jr.) and Nathaniel Ayers (Jamie Foxx) have absolutely nothing in common, unless you count a propensity for stringing words together — which doesn’t count, because Lopez gets paid for it by the Los Angeles Times, while Ayers’ disjointed, rambling volubility is largely incomprehensible.

Earth (2007)

Welcome to Earth. Adapted by directors Alastair Fothergill and Mark Linfield from producer Fothergill’s groundbreaking 550-minute BBC miniseries “Planet Earth,” Earth offers an impressive selection of some of the most astounding images ever captured of the natural world. Many of the film’s sights had never been witnessed or photographed before Fothergill and the BBC Natural History Unit set out to create “the definitive look at the diversity of our planet,” as “Planet Earth” is not unreasonably billed.

The Hiding Place (1975)

Thirty years after its original release, The Hiding Place remains one of the best films ever produced by a faith-based group (Billy Graham’s World Wide Pictures).

Slumdog Millionaire (2008)

Celebrated by fans as the “feel-good” film of 2008 and damned by skeptics as “poverty porn,” Best Picture winner Slumdog Millionaire is, I think, neither of these. It’s a wrenching fairy tale, a yarn rife with desperate want, loyalty and love, a fable of the vagaries of life that are often cruel but sometimes unexpectedly, sublimely kind.

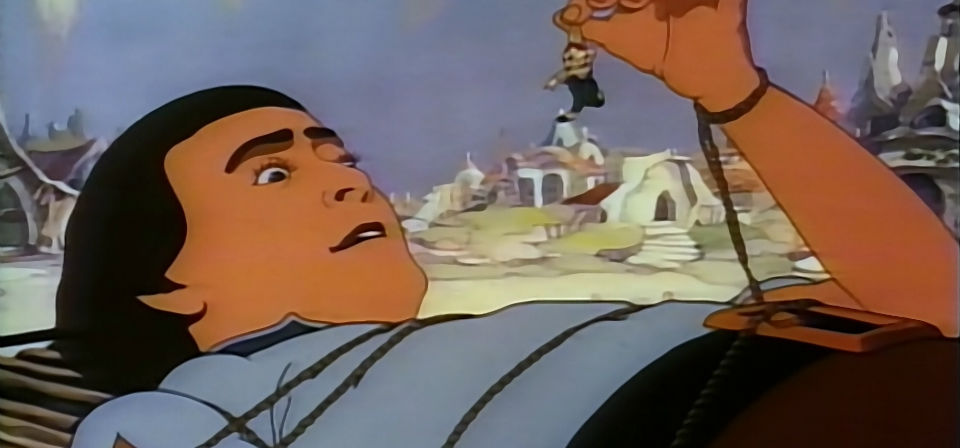

Gulliver’s Travels (1939)

Coming on the heels of Disney’s landmark Snow White, Gulliver’s Travels, from rival Fleischer Studios, is an intriguing case study in the elusive gap between decent work by talented animators and a successful and satisfying film.

Monsters vs. Aliens (2009)

As a tale of female empowerment and male comeuppance, Monsters vs. Aliens might have been provocative, like, 50 years ago. Today, nothing seems more subversive — and unlikely — than a family film with a heroic leading man who’s the equal of the leading lady — one boys can look up to without having to learn a lesson about male weakness. Now that’s a movie I’d like to see.

Bolt (2008)

It’s not quite Pixar grade, but Bolt blots out tepid memories of the likes of Chicken Little and Home on the Range, standing comfortably beside the likes of Kung Fu Panda and Horton Hears a Who in the race for second-best computer-animated family film of 2008.

Return From Witch Mountain (1978)

Better structured and faster-moving than its predecessor, the sequel has more energy and wit in one sequence — the gold theft at the museum, in which a rolling stagecoach and floating manniquins evoke scenes from a Western — than all the special effects in the first movie combined.

Escape to Witch Mountain (1975)

One of the most popular Disney films of its era, Escape to Witch Mountain only loosely follows Alexander Key’s comparatively dark original tale about a pair of troubled orphans escaping a grim juvenile-hall orphanage and a sinister pursuer with the help of a heroic Catholic priest.

Race to Witch Mountain (2009)

Rather than a coming of age story, then, Race to Witch Mountain is a dark family action-adventure movie, with moderate doses of X-Files paranoia and Galaxy Quest sci-fi fandom satire, and a sometimes obnoxious rock soundtrack. It’s slicker, darker and funnier than the original films, though wall-to-wall action makes it a bit of a one-trick pony, and prevents the characters from catching their breath and displaying more than one side.

Oliver & Company (1988)

The last gasp of Disney Animation’s post-Walt malaise before the 1990s Disney renaissance, Oliver & Company borrows names and vague situations from Oliver Twist, but in place of Dickens’s sentiment and Victorian moralizing Oliver has only a misguided stab at “attitude.”

Australia (2008)

Much like Scorsese’s Gangs of New York, it’s a film that has been long labored over, and the artist’s love of the material is clear, but the inspiration has been lost along the way and the characters reduced to cartoony types.

Pinocchio (1940)

Emotionally resonant, visually dazzling, imaginatively captivating, thematically rich, Walt Disney’s Pinocchio may just be the greatest of all the early Disney masterpieces, possibly outshining Snow White, Fantasia and Bambi.

Watchmen (2009)

The movie is an impressive work of transposition, but I can’t recommend it. Excessively brutal and sexually graphic as well as nihilistic and and antiheroic, it’s a thoroughgoing deconstruction of humanity as well as heroism, one that takes its world apart without putting it back together again. There are things to admire here, but Watchmen doesn’t make me care. If you can’t care about characters facing the end of the world, perhaps it’s time to turn back the clock and move on.

Coraline (2009)

With its dark tale of changeling parents and imprisoned souls, Coraline comes closer to the spirit of the traditional European fairy tale than perhaps any other film, animated or otherwise, in recent memory.

Taken (2008)

Well-crafted but improbable action set pieces cast the 56-year-old Neeson as an essentially indomitable force taking on and prevailing against almost any number of gun-toting assailants — like Jason Bourne, Bryan combines boundless resourcefulness with essentially indomitable physical prowess — but the film’s emotional force rests on the comparatively persuasive setup.

Recent

- Benoit Blanc goes to church: Mysteries and faith in Wake Up Dead Man

- Are there too many Jesus movies?

- Antidote to the digital revolution: Carlo Acutis: Roadmap to Reality

- “Not I, But God”: Interview with Carlo Acutis: Roadmap to Reality director Tim Moriarty

- Gunn’s Superman is silly and sincere, and that’s good. It could be smarter.

Home Video

Copyright © 2000– Steven D. Greydanus. All rights reserved.