Articles

2005: The year in reviews

Like a lot of moviegoers, I spent a fair bit of time this year wringing my hands over the quality of the movies. Looking back, though, it seems to me that the family-film pattern mirrors the overall year: a dearth of A-level films, perhaps, but a bumper crop of B-pluses.

Stories of Karol: Telling the life of a man who became pope

Karol: A Man Who Became Pope isn’t the first TV movie on the life of Karol Wojtyla, the future Pope John Paul II — but among the new crop of Pope movies coming in the wake of the Holy Father’s death, it’s not only the first, but also the only one seen and praised both by Benedict XVI and John Paul II himself.

Narnia Filmmakers Hype the Fantasy, Hedge the Faith

A lot of thought and effort went into getting the feel, the look, the period and the characters of C. S. Lewis’s beloved fairy tale The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe right for the screen… At the same time, judging from the unanimous testimony of the filmmakers, one crucial element of the book was not a consideration one way or the other in adapting the story: its religious significance.

Into the Wardrobe: Bringing Narnia to Life

Before there are centaurs, fauns, or even a lamp-post incongruously burning in the middle of nowhere to establish that the forest beyond the wardrobe door is no ordinary wood, Andrew Adamson’s The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe creates the magic of the wood and the wardrobe with the enchantment on the face of young Georgie Henley, who plays Lucy Pevensie, as she gets her first glimpse of the Narnian wood.

The Harold Lloyd Comedy Collection

For fans of silent comedy, it’s the DVD event of the decade: Harold Lloyd, the “Third Genius” of silent comedy (Chaplin and Keaton being the other two), until now almost totally unavailable on DVD, at last enters the modern home-video age in grand style with the The Harold Lloyd Comedy Collection.

A Nice Guy Finishes First

The Greatest Game Ever Played, starring Shia LaBeouf (Holes, Constantine) and directed by Bill Paxton from a screenplay by Mark Frost adapting his own best-selling book, isn’t just the true story of a dramatic championship playoff. It’s also the story of a revolution in popular culture, of how a poor, unassuming youth helped democratize the most aristocratic of games, transforming golf from the exclusive domain of private clubs and wealthy elites to a popular middle-class pastime played on public courses.

The Exorcism of Emily Rose: Scott Derrickson, Paul Harris Boardman, Laura Linney, Jennifer Carpenter

There are no scenes of spinning heads, projectile pea-soup vomiting, or levitating beds in The Exorcism of Emily Rose (opening September 9), starring Laura Linney, Tom Wilkinson, Jennifer Carpenter, and Campbell Scott.

“I have a hard time making any decision whatsoever”

For German filmmaker Volker Schlöndorff, the appeal of making The Ninth Day, a fact-inspired film about a priest in a Nazi concentration camp who is briefly released, goes back over five decades to Schlöndorff’s film-club days at a Jesuit boarding school, where he first encountered Carl Dreyer’s silent masterpiece, The Passion of Joan of Arc.

An American mythology: Why Star Wars still matters

Star Wars is pop mythology — a "McMyth," as a recent critical article put it — but in our McCulture even a McMyth can be vastly preferable to no myth at all, and certainly to other, less wholesome mythologies (e.g., the Matrix trilogy). Even for those who generally prefer more traditional fare, there is still much to enjoy and appreciate in these half-baked, stunningly mounted fantasies of good and evil in a galaxy far, far away.

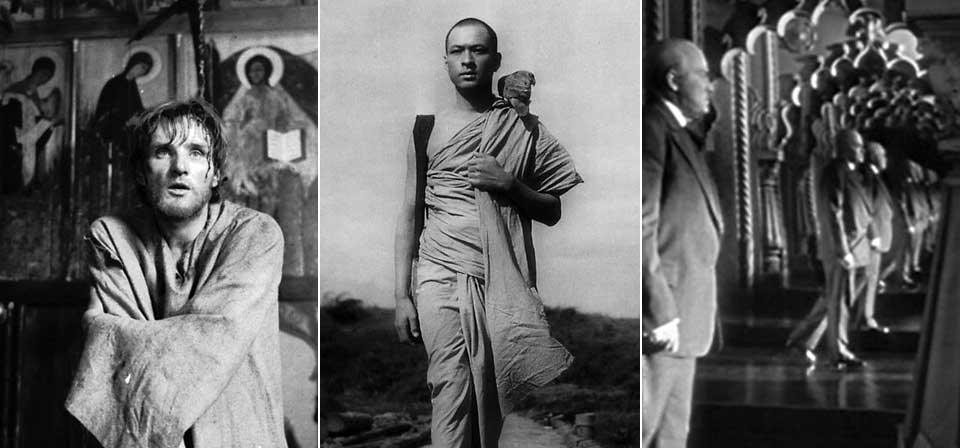

The Vatican Film List

The pope’s remarks were both forward looking, speaking to the potential of cinema to become “a more and more positive factor in the development of individuals and a stimulus for the conscience of society as a whole,” and also historically minded, speaking positively of the praiseworthy contributions of “many worthwhile productions during the first hundred years of [the cinema’s] existence.”

2004: The year in reviews

Did anything worth caring about come to cineplex screens? Anything anyone will be talking about or revisiting five or ten years from now?

Triple Threat: Fox’s Spring 2005 Family Film Lineup

Typically, the spring movie season has at most one decent film for family audiences. Last year it was Two Brothers; offerings from previous years included Holes (2003), Ice Age (2002), Spy Kids (2001), and The Emperor’s New Groove (2000).

2003: The year in reviews

It was a rough year at the movies for the Catholic Church.

Faith and Film in the Post-Passion Era

Constantine might sound like the latest entry in Hollywood’s string of violent costume dramas (Alexander, Troy, King Arthur), but it’s not actually about the Roman emperor who was the subject of such religious films as Constantine and the Cross. In this film, instead of a sign in the sky, the cross is a weapon in the ero’s hands. Starring Keanu Reeves, Constantine is a sort of a cross between Hellboy and The Exorcist with some Matrix attitude thrown in, a violent R-rated action-thriller of the supernatural based on the DC/Vertigo comic book Hellblazer, about a cynical demon-hunter antihero who’s literally been to hell and back. Though he knows that what God expects is belief, self-sacrifice, and repentance, he is futilely trying to earn his way into God’s good graces.

Sports and Coaching, Life and Death: Coach Carter & Million Dollar Baby

Coach Carter is based on the real-life story of Ken Carter, an uncompromising high-school basketball coach at a tough urban school who requires more from his players than great basketball. He insists that they sign contracts requiring them to attend classes, sit in the front row, and maintain a C-plus grade point average or better — and is willing to lock the gym and forfeits games if they fall behind in their classes.

The Kinsey controversy

The life and work of Dr. Alfred C. Kinsey, the Indiana University entomologist turned pioneering sexologist, has provoked accounts and interpretations as divergent, and as bitterly contested, as John Kerry’s Vietnam service in the last election. And, while it’s true that Kinsey’s work warrants such scrutiny, it’s also true that this only makes the task of weeding through the arguments more daunting.

“Pick The Right One to be in the Foxhole With”

It’s not just a buzzword, either. There’s a special hand gesture that goes along with it. First you hold your hands up, palms outward, fingers spread apart. This where we are: no synergy. Then you clasp your hands into fists with the tips of the fingers of each hand inside the fist of the other hand, so that your hands make a sort of "S" shape. This is where we need to get to: synergy. Get it? (If you think this kind of thing doesn’t really pass for deep thought in corporate convention halls and conference rooms, you don’t know corporate America.)

Joy to the World: A Christmas Carol and the attack on — and defense of — Christmas

Scrooge’s conversion, like many conversions, is just such a dramatic revelation out of crisis, "as sudden as the conversion of a man at a Salvation Army meeting," says Chesterton, adding slyly, "It is true that the man at the Salvation Army meeting would probably be converted from the punch bowl; whereas Scrooge was converted to it. That only means that Scrooge and Dickens represented a higher and more historic Christianity" ("Christmas Books").

“I get so frustrated with Hollywood”: Paul Feig on I Am David

It isn’t only Jim Caviezel, the Christ of The Passion, here another nobly self-sacrificial prisoner who freely allows himself to be wrongly condemned in order to save another. It’s also the actor who plays the complex, conflicted official who suspects his prisoner is innocent but must pass judgment anyway — Pontius Pilate in The Passion, "The Man" in I Am David. In both films, the role went to Bulgarian actor Hristo Shopov.

Jackie Chan: An Appreciation

The fact is, Jackie’s appeal is hard to sum up in a single sentence. Ask five different Jackie Chan fans what they like about him, and you may get five different answers.

Recent

- Benoit Blanc goes to church: Mysteries and faith in Wake Up Dead Man

- Are there too many Jesus movies?

- Antidote to the digital revolution: Carlo Acutis: Roadmap to Reality

- “Not I, But God”: Interview with Carlo Acutis: Roadmap to Reality director Tim Moriarty

- Gunn’s Superman is silly and sincere, and that’s good. It could be smarter.

Home Video

Copyright © 2000– Steven D. Greydanus. All rights reserved.