Articles

Can Muslims and Christians coexist? Of Gods and Men

Of Gods and Men is the most extraordinary cinematic depiction of the Christian ideal in at least the last quarter century. It also depicts something of the variety of expressions in the Islamic world.

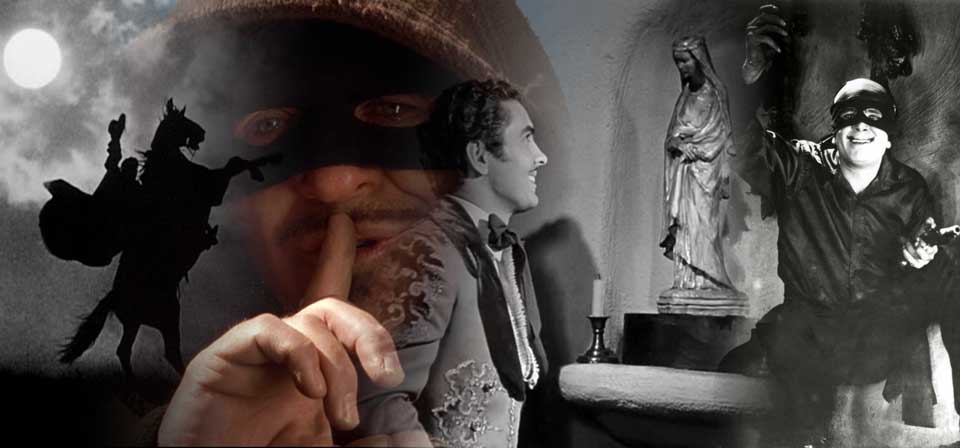

Zorro: Before Daredevil or Nightcrawler, the first superhero ever was Catholic

“He has been many different men,” Antonio Banderas tells Catherine Zeta-Jones in the last scene of the rousing 1998 action movie The Mask of Zorro.

Catholic deacon whose drilling company helped rescue The 33: “God drilled that hole”

Hall doesn’t want credit; as far as he’s concerned, the rescue was God’s work, not his.

The priest, the student, and the swastika

Both films revolve around a number of tense cat-and-mouse interviews between the believing protagonist and a shrewd Nazi antagonist … The interviews in both films are a clash of worldviews.

You’re an institution, Charlie Brown

“Peanuts”’ appeal was universal: It was beloved by young and old, by the intelligentsia as well as the masses; it was the definition of mainstream, yet it was also embraced by the counterculture. It was bitterly pessimistic, yet never succumbed to the despair and nihilism of, say, “Dilbert” or “Pearls Before Swine.”

Vampires, demons and the cross: Catholicism and horror

“When it comes to fighting vampires and performing exorcisms, the Roman Catholic Church has the heavy artillery” is how Roger Ebert opened his review of John Carpenter’s Vampires.

Looking back at Back to the Future

If the early scenes with Marty’s mother suggest that parents sometimes try to hold their children to a standard they never tried to meet themselves, the parking scene suggests that the reverse may also be the case: Children may want their parents to embody a higher standard than they want for themselves.

Bending the air: Defying gravity in “Avatar,” Star Wars, Miyazaki and more

There is a sense in which “Avatar: The Last Airbender” is for my children in part what Star Wars was for my generation: a new and enthralling mythology about a young hero with a mysterious power slowly learning to channel that power to fight against a tyrannical empire.

The theology and philosophy of Avengers: Age of Ultron

We aren’t exactly talking The Matrix here, but it’s been awhile since a Hollywood popcorn action movie elicited such a range of theological and philosophical analysis.

“Franciscan” movies for Pope Francis’ US visit

Much like Pope Francis himself at times — or even like Jesus himself — Saint Francis of Assisi has often been made into an avatar or mascot of people’s likes (or dislikes) rather than being recognized as the surprising, vibrant figure he really was.

How James Bond lost his soul: Casino Royale

Casino is more than a reboot: It’s also a kind of origin story, based on the first Ian Fleming novel. As such, it’s the story of how James Bond lost his soul, or whatever was left of it, at the very moment when he dared to hope for redemption.

The taking of an oath: Marriage, annulments, Kim Davis, and A Man for All Seasons

The name of Saint Thomas More has cropped up in recent discussion of current events as never since — well, if not since the English Reformation, at any rate probably since one of my all-time favorite films, A Man for All Seasons, won six Academy Awards at the 1966 Oscars, including Best Picture, Best Director (Fred Zinnemann), and Best Actor (Paul Scofield).

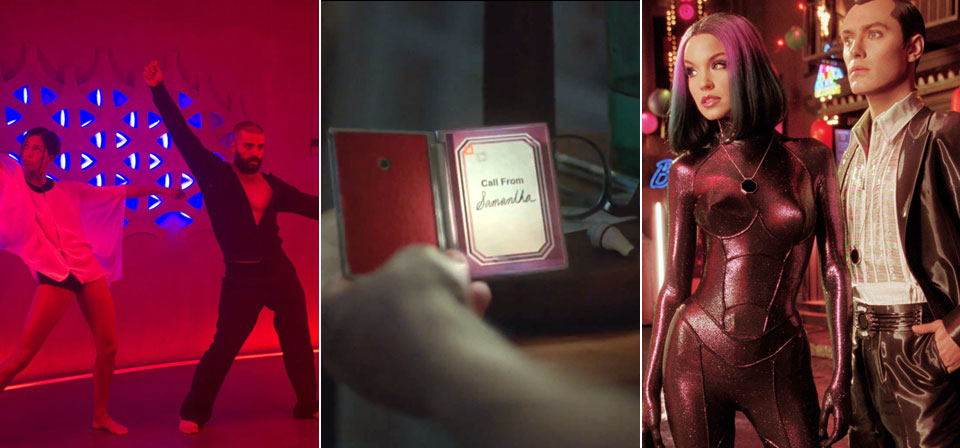

“Brother Ass” or “stupid apes”? Transhumanism, the Imago Dei and Hollywood

As technology progresses and the culture and the Gospel continue to draw further apart, transhumanist aspirations flourish, both as a worldview and in the world of popular culture.

Gun culture and Hollywood: Turning away from violence

All violence is not the same. There are obvious, important differences between realistic war violence, violence in a serious social drama, cartoon violence in an action movie, horrific violence in a crime movie, slapstick violence in a comedy and so forth. Ultimately, though, I think it’s important to give ourselves regular breaks from violence of any kind. Violence is unavoidably part of human nature, but it’s far from the most interesting part.

The spiritually aware cinema of Jean‑Pierre and Luc Dardenne

The Dardennes’ films generally have redemptive arcs of some sort, or at least the hope of redemption — though there are no traditional happy endings, only hopeful new beginnings. Theologians ponder the mystery of evil; the Dardennes are intrigued by the mystery of goodness.

The Train: When is art worth dying for?

Are manmade things ever worth dying for? How do you weigh the value of art or artifacts against the value of human life? On the one hand, human life is sacred; things are just things. On the other, the cultural heritage of a people is an irreplaceable treasure that belongs not only to the whole community, but to all future generations.

“We are not things”: Mad Max: Fury Road and commodifying human life

In another movie, a line like “We are not things” could be a platitude, but in the context of vividly imagined atrocities with unnerving echoes of recent headlines, this simple affirmation is fraught with topical power that has only grown in the months since the film’s theatrical debut.

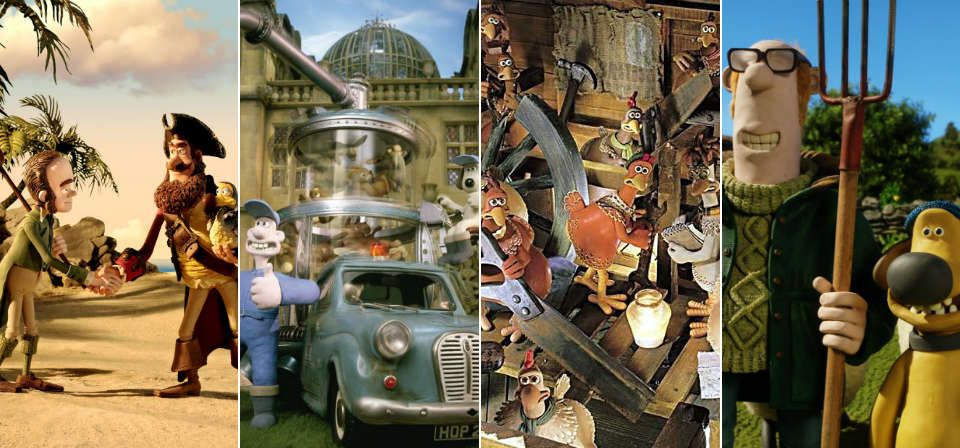

Shaun the Sheep and beyond: The magic of Aardman

For the Aardman filmmakers, it seems that inspiration and the tactile work of stop-motion go hand in hand.

The greatest American films: Film critics vs. the Vatican

One much-noted point about the BBC list is how few Academy Award Best Picture winners made the list. Naturally, I’m interested in a different comparison: How does the BBC list compare to the 1995 Vatican film list?

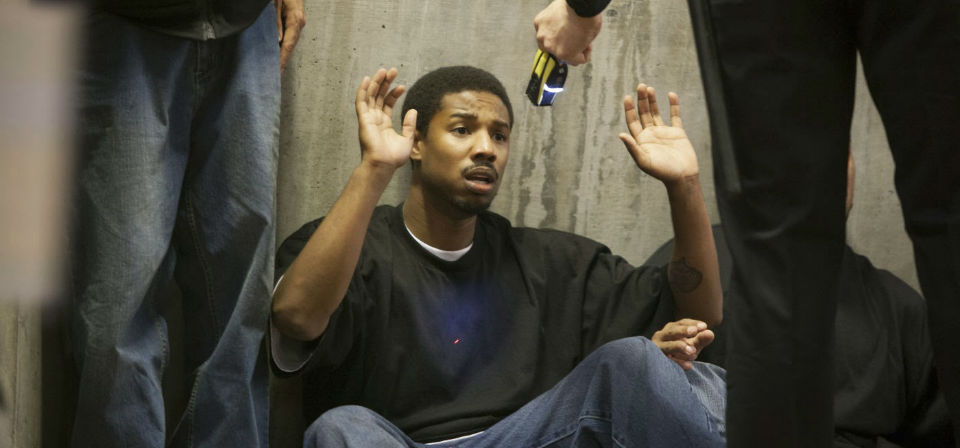

Black lives matter: Watching Fruitvale Station one year after Eric Garner

I recently rewatched Fruitvale Station (2013), first-time director Ryan Coogler’s shattering Sundance winner, with my oldest son, who has since gotten his driver’s license. Some day he will face that inevitable first traffic stop, and I want him to be aware just how different that encounter will be for him, with his bleached complexion and shining towheaded crown, than for many young men in the minority neighborhoods all around us.

Recent

- Benoit Blanc goes to church: Mysteries and faith in Wake Up Dead Man

- Are there too many Jesus movies?

- Antidote to the digital revolution: Carlo Acutis: Roadmap to Reality

- “Not I, But God”: Interview with Carlo Acutis: Roadmap to Reality director Tim Moriarty

- Gunn’s Superman is silly and sincere, and that’s good. It could be smarter.

Home Video

Copyright © 2000– Steven D. Greydanus. All rights reserved.