Articles

The easygoing Catholicism of Return to Me

Return to Me has an easygoing Catholic vibe akin, but not identical, to Golden Age Hollywood piety; in fact, the movie blends nostalgia and irreverence for the Catholic Hollywood of Bing Crosby’s era.

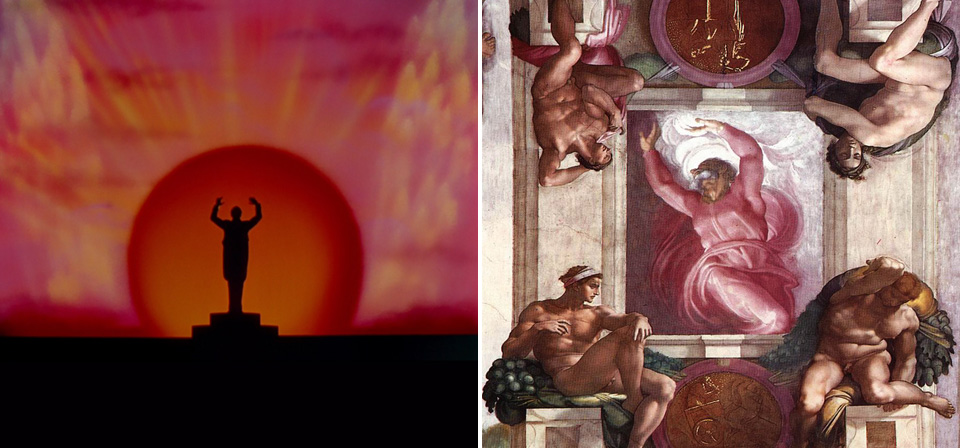

Fantasia: The Sistine Chapel of Disney animation

Among a few Disney films deserving of the title “masterpiece,” Fantasia remains a unique achievement.

2014: The year in reviews

The quest for justice and harmony echoed through the best films of 2014, playing out in various arenas: social, domestic and spiritual.

Raking through the ashes of unbelief: Woody Allen’s lost spark

Woody Allen keeps telling us God is dead, but he also keeps compulsively burying him.

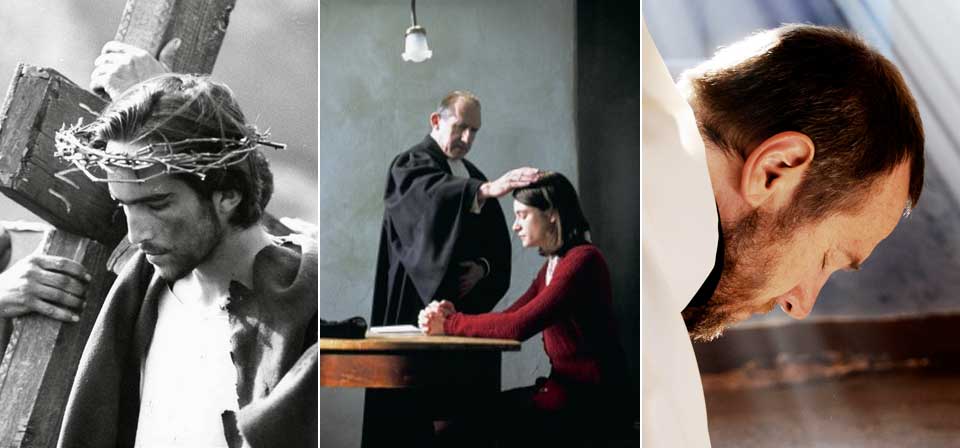

The Church on screen in 2014: Not a bad year for Catholics

By mid-year I would have predicted that Mendoza would surely prove to be the best big-screen priest of 2014 — but Brendan Gleeson’s Rev. Lavelle in John Michael McDonagh’s Calvary proved me wrong.

Christmas Day is over … time to watch Christmas movies!

What can Catholics do to keep things Christmasy until mid-January? Among other things, I suggest keeping the tree and the lights lit until at least January 6, if not the following Sunday — and saving the Christmas movies till after Christmas day.

The trouble with Christmas movies

“What are your favorite Christmas movies?” As a Catholic film critic, I get this question several times every December, often on the air or via social media. The question, alas, touches on a sore subject for me.

How The Hobbit: The Battle of the Five Armies betrays Tolkien’s Catholic themes — and his religious fans

Changes like these are sadly typical of the Hobbit prequel trilogy, which is far cruder and less sensitive to the charm and beauty of its source material than the Lord of the Rings films were. As bad as Christopher Tolkien’s fears in 2012 about The Hobbit films might have been, the reality is worse.

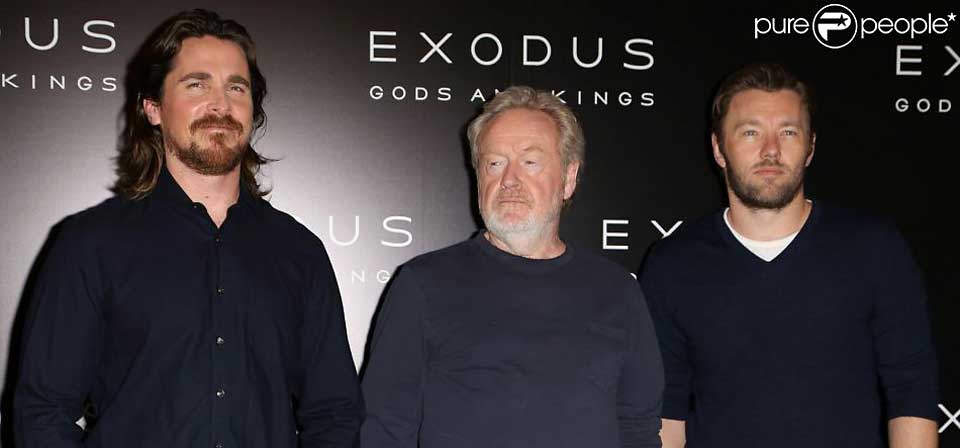

Exodus: Gods and Kings: Theological reflections

It’s a movie with many problems, like most of Scott’s recent epics (Prometheus, Robin Hood, Kingdom of Heaven), but Scott has a better story to work with here and adds something of value to the world of Bible cinema.

Interview: Exodus: Gods and Kings filmmakers Ridley Scott, Christian Bale and Joel Edgerton

Ridley Scott’s Exodus: Gods and Kings (in theaters Dec. 12) is the year’s second major Old Testament epic from a director who is not a believer — but don’t get Scott started on Noah’s rock-monster Watchers.

Moses at the movies

The Exodus is probably the Bible’s most cinema-ready story, the perfect Bible-movie subject. Unlike the stories of Noah, Abraham, David, Jesus, Peter, or Paul, it offers a sustained narrative structure, with a clear central conflict between a strong hero and a strong villain, building to a series of grand climaxes.

How Disney’s Maleficent subverts the Christian symbolism of Sleeping Beauty

Give me princesses like Leia from Star Wars, Merida from Brave or Tiana from The Princess and the Frog any day. But there’s a difference between creative revisionism and simple inversion.

Dystopia, The Hunger Games and the critique of the culture of death

The word utopia was coined by St. Thomas More in his book of that name — an important and enigmatic work of fiction and political philosophy generally understood as some sort of satire.

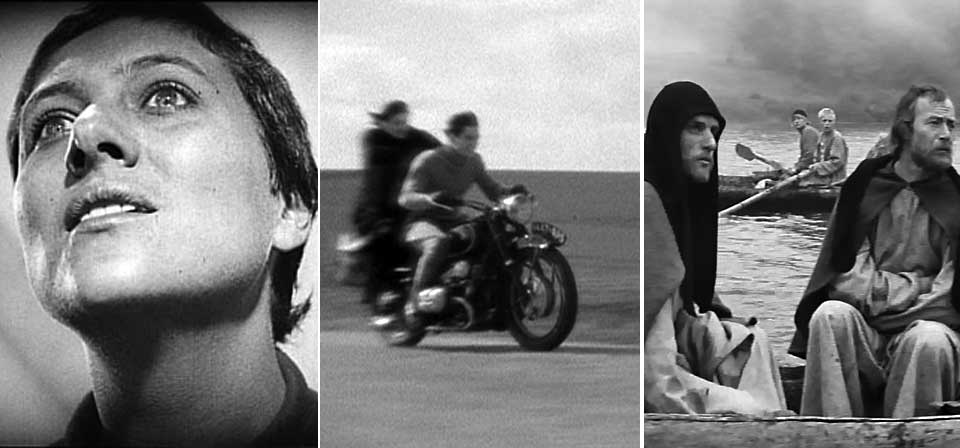

Seeking accessible saint movies … for less arty viewers

A reader writes: “I am looking for easy-to-approach religious movies, especially ones on saints. Intellectually challenging, subtitled, confusingly artistic movies seem to dominate. While I really love those types of movies, I am trying to find films for my Bible study group … We tried the first half of Diary of a Country Priest, and I worried one might try to smother herself with my sofa pillow to end her misery. Do you have any thoughts?”

Taking themselves lightly: “The Flying Nun” and The Reluctant Saint

If “The Flying Nun” is a bit too, well, flighty for some tastes, consider another 1960s production about a consecrated religious — a real-life one in this case, and a canonized saint — given to slipping the surly bonds of earth.

Religious filmmakers explore — and cross-examine — faith

Strikingly, where the religious films of nonbelievers often feature idealized religious characters more or less certain in their faith, films by believers often put their religious characters’ faith to a more existential test.

Do atheists and agnostics make the best religious films?

One of the noblest functions of art is the invitation to empathy: an invitation extended not only to the audience, but also to the artist.

From the Crusades to Columbus: Religion in Ridley Scott’s Historical Epics

A self-described atheist, Sir Ridley Scott has developed a generally bleak vision of religion, particularly the Judeo-Christian tradition, throughout his work, above all in historical sagas like Robin Hood (2010) and 1492: Conquest of Paradise (1992).

Two Very Different Responses to Parenthood: Chef and Obvious Child

Among this summer’s successful indies were a pair of R-rated comedies — each from a filmmaker serving as writer, director and star — depicting two very different responses to the formidable responsibilities of parenthood.

Jewish/Catholic: Religious Identity, Fluidity and the Holocaust

“One is Christian or Jewish, not both.” So says the chief rabbi of Paris in The Jewish Cardinal (2013), Israeli-born filmmaker Ilan Duran Cohen’s biopic about Cardinal Jean-Marie Lustiger (Laurent Lucas) — a Jewish convert to Catholicism who insisted on religious dual citizenship, embracing Catholicism without rejecting Judaism.

Recent

- Benoit Blanc goes to church: Mysteries and faith in Wake Up Dead Man

- Are there too many Jesus movies?

- Antidote to the digital revolution: Carlo Acutis: Roadmap to Reality

- “Not I, But God”: Interview with Carlo Acutis: Roadmap to Reality director Tim Moriarty

- Gunn’s Superman is silly and sincere, and that’s good. It could be smarter.

Home Video

Copyright © 2000– Steven D. Greydanus. All rights reserved.